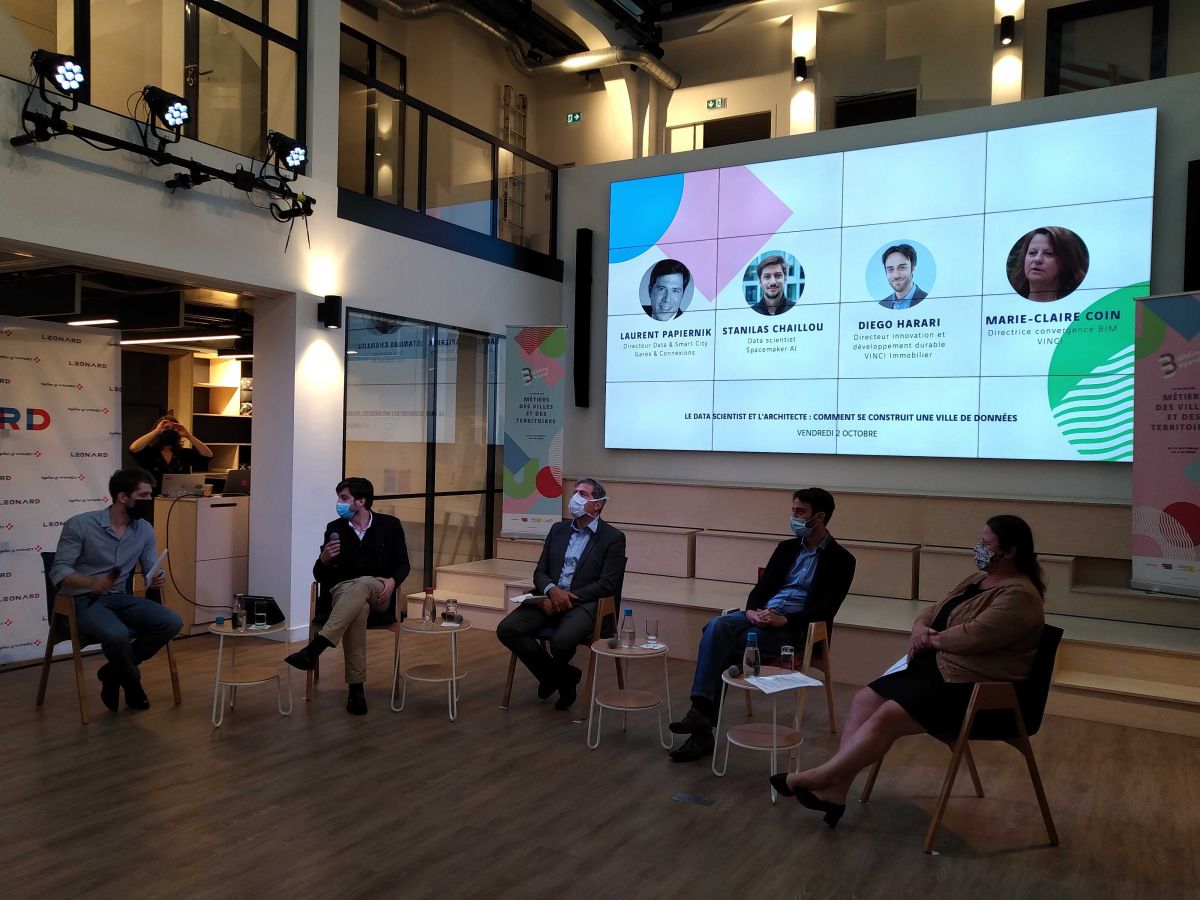

Leonard brought together a variety of viewpoints for this round table, ranging from property development to project development in cities, and on to operating the different kinds of infrastructure. The speakers were Laurent Papiernik, Chief Data and Smart City Officer at SNCF Gares & Connexions, Stanislas Chaillou, an architect and data scientist at Spacemaker AI, Diego Harari, Innovation and Sustainable Development Director at VINCI Immobilier, and Marie-Claire Coin, BIM Convergence Director at VINCI.

The industry is still struggling to tap into data, so how do we go about building the data city of tomorrow?

Before anything else, what are data cities? Laurent Papiernik defines them as cities that can examine, feel, fix and organise themselves. A data city is able to build services swiftly and effortlessly, using digital technology. It can enlist all its capabilities in real time to trigger maintenance and repair work.

Stanislas Chaillou, who handles this kind of data on a daily basis, adds that the current circumstances are nudging us towards parametricism. Data could be used to optimise a set of criteria in order to find the best possible response to a given situation. The people designing tomorrow’s cities could rely on artificial intelligence combined with statistical modeling methods to handle this data and information flow.

This works for every business line: Diego Harari says that property developers are also keen on data and artificial intelligence. Digital technology is helping to produce more leads and thereby sell more properties. Sales and customer service teams embarked on their digital transformation some time ago. But, today, the customer experience can be tailored: AI, for instance, can create a customised plan for startup HabX’s clients.

So digital technology has put the industry in a position to take a leap towards the city of tomorrow. But not as far as the data city just yet, Marie-Claire Coin adds. She reminds participants that BIM stands for Building Information Modelling, meaning that it uses information rather than data. Unlike data, information is functional, can be qualified, can be structured and can answer a given question. BIM isn’t the right tool to build the data city, at least at this point. According to VINCI’s BIM Convergence Director, there is still a considerable way to go before artificial intelligence can be used to build the data city.

The inflow of city-related data

Stanislas Chaillou lists the fundamental requirements to design a city, namely geometric resolution, performance and matching form to function. It is essential to keep all these aspects in mind when processing data. Otherwise, we might continue to only automate design. In other words, only form will be efficient and optimised. Artificial intelligence needs to do more than that: build a scalable city that can adapt its form and the use of the space in it.

Diego Harari believes that artificial intelligence comfortably covers the full range of possibilities in design. Every step change in digital technology brings about new ways of using it. Examples include the shift in the notion of ownership with the advent of shared cars and bicycles, and e-commerce, which opened the door to develop connected infrastructure enabling high-value-added services.

Building the data city of the future seems doable with artificial intelligence. But it is nevertheless a complex process and requires a wide range of areas of expertise. At SNCF Gares & Connexions, expertise overlaps with policy from the institutions overseeing each department. Its architects, urban planners, designers and flow managers liaise to create and operate frugal buildings and infrastructure using digital technology.

Marie-Claire Coin points out that digital technology (and the continuous inflow of information from and about the people using the city) is bringing about a paradox: a tendency to focus more on the micro perspective and less on the macro one. Digital technology makes it possible to zoom in on information that is opening up new prospects and changing the dimension of a city.

Have architects, developers and builders been left behind by the new tech players?

New tech players are venturing into the building and civil engineering sector. At first, they only supplied software. Now, however, they are hoping to standardise processes and supply data infrastructure for modular construction. Katerra, for instance, is developing its own projects and becoming a potential rival for builders. There is also a chance these new players will team up with construction companies and help them blaze new trails instead of competing with them, as Spacemaker is doing. Stanislas Chaillou argues that architects will continue to gain ground because artificial intelligence still lacks the skills to replace a human being at the helm of the project. Moreover, human specialists are still the go-to people on projects and AI won’t be in a position to claim that position for a long time yet.

Cooperating so GAFA doesn’t capture the data

Stanislas Chaillou and Diego Harari agree that the fact that the construction industry is variegated and complex is not stopping digital players from trying to move in. They have the financial resources to hire people who know our trades and our sector. But entrusting GAFA with building cities makes no sense because they lack the expertise that architects, builders and developers have. Diego Harari insists on the urgent need to start thinking about the strategic assets we need to prevent that scenario from materialising and enable the “traditional” players to grow. Developers, he continues, should upgrade the experience they provide in order to take up positions in the construction of the data city.

Laurent Papiernik adds that GAFA are only vaguely interested in bricks and mortar, and reluctant to take on complex issues that have little to do with the digital sphere. To push back when they try to break in, he suggests sharing all the available information about flows so as to improve the way the system works. The data city needs to be homogeneous and urban spaces need to cooperate to create a digital continuum in an urban area. The data city won’t happen if everyone works towards it in their own corner. The construction industry’s “traditional” trades will only hold on to their place in it if they plan the data city properly and spur it by cooperating.

At the end of the day, the key message from this third Building Beyond festival is “people building the city of the future, cooperate!”

Further reading: A construction revolution? Builders 4.0, get ready!, a report on the Building Beyond conference about new digital technologies in construction.