Half of the 46 million tons of waste produced each year by the construction industry in France comes from demolition and 13% from new construction. However, as waste recovery is increasingly used to reduce the industry’s carbon footprint, another approach is simply to produce less waste. This means renovating and rehabilitating existing buildings rather than destroying them.

Warehouses have been turned into breweries and factories into collaborative workspaces; the Grand Hôtel Dieu, a former hospital in Lyon, France, has now become a modern building comprising of new and renovated offices, shops, a museum and a conference centre. And the former El Ateneo theatre in Buenos Aires, Argentina, which dates back to the 19th century, has recently been converted into a bookshop.

New from old

The aforementioned projects have something in common: they are a showcase for the rehabilitation of buildings that are often a hundred years old, and have undergone a radical change of use. Paradoxically, the practice is less common for more recent buildings from the strong urban growth of the 1950s onwards.

“Concrete low-income housing blocks built in the 1970s have a life expectancy of a few decades, whereas Haussmann buildings are still standing, a century after they were built,” says Tanguy Mulliez, director of business development at Etamine, a consultancy specialising in environmental design in construction. “This is due to the quality of the construction and the materials used, but also to the way new buildings are constructed today. Everything has been calculated down to the last millimeter to fit in with the construction costs, so there is no room for manoeuvre in terms of ceiling height or built surface area. There was more flexibility before, which paradoxically means that old buildings are more adaptable, and it is easier to find a new use for them,” he explains.

Towards reversible construction

This widely shared view now forms the basis of reversible architecture, whose aim is to design the construction of buildings upfront to make them versatile. This means transforming an office building into a hotel or a housing complex, for instance.

“Faced with the climate crisis, we are going to have less land to build on. There will be increasing regulations to limit soil sealing, which will reduce construction opportunities and force us to deal with existing buildings in the future, by which I mean those we are building today. Reversible construction guarantees less destruction in the future. If buildings can be converted, we won’t have to raze them, which will generate less waste and CO2,” explains Patrick Rubin, who runs Canal Architecture consultancy. For several years, they have been conducting research and piloting projects in reversible architecture.

Housing or offices, why choose?

According to Patrick Rubin, constructing a reversible building means that it can accommodate either housing or offices, when the two options currently operate in completely separate universes. This means challenging standards such as ceiling height. “Today, an apartment building has a 2.50 m ceiling height, and 3.30 m for an office building. These international standards have been in place since the Second World War. The greater height of office buildings was meant to allow for a false floor and ceiling, to hide ducts and pipes. But as the Pompidou Centre and Starbucks have shown, this can be done away with. That said, higher ceilings mean more light, better air circulation and more comfort. What we offer is a generic building with a 2.70 m ceiling, which can be used for either purpose.“

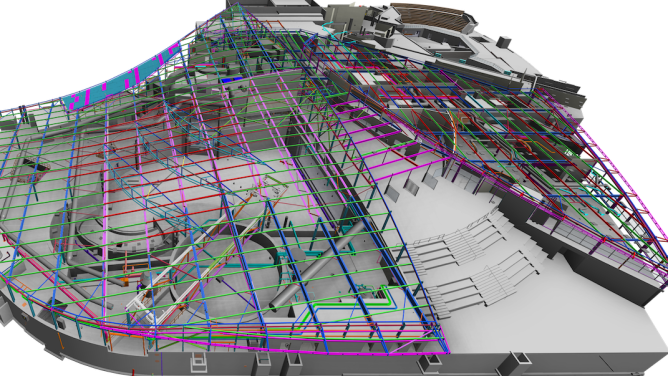

The ceiling height is one of many factors being challenged. Canal Architecture also experiments with building width, fire escape staircases and office standards, as well as opting for technical columns over load-bearing walls. The consultancy is currently working on the Bordeaux-Euratlantique project, a fully reversible building based on Canal Architecture’s 2017 study Construire réversible.

Buildings that can be completely dismantled

In order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past Olympic sites building, which have since proved obsolete in most cases the Paris City Council wants to make sure that the infrastructures purpose-built for the 2024 Olympics will have a second life. The engineering firm Etamine is working with VINCI Construction on the Universeine Olympic Village in Saint Denis with this in mind. “After the Games, some of the space will be converted into habitation to create 633 flats. The materials used in this conversion will come partly from the circular economy, or recycled in the circular economy,” explains Gaia Alliney, project manager at Etamine.

A building does not have to stay in one piece to live several lives. Long-term architecture means constructing buildings that can be completely dismantled, with every piece of equipment and material fully reusable. The People’s Pavilion, designed by the Dutch Bureau SLA and Overtreders W for Dutch Design Week in 2017, was made entirely of borrowed building materials that were returned to their owners after the event.

So is the Koodaaram Pavilion, built for the 2018 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Asia’s largest contemporary art festival. Fully dismountable and made of reusable materials, it was designed for nature to reclaim the site within two years.

The norms of the circular economy, which tend to be applied to materials and waste management practices first, could well herald a major transformation in architecture and building design, ushering in the era of the mutant building.