Three types of technology

Electric vehicles that can be charged while driving. This is exactly what electric roads promise, and is currently embodied in three types of more or less mature technology. The first, which is undoubtedly the most tried and tested, consists in installing overhead catenaries, similar to those used on railways. While it’s an effective solution, it’s limited to tall vehicles and also requires vehicles to have pantographs installed. eHighway, developed by Siemens, is undoubtedly the most advanced project of this type.

The second track technology can be found under vehicles, thanks to ground-level power through rail. Vehicles must be equipped with capture pads, just like those tiny cars that whizz around on toy tracks. To date, the trams in Bordeaux, Angers and Tours are amongst the rare concrete examples of ground-level power supply, the ground-rail conduction technology developed by the French company Alstom. The discreet nature of this technology has also won over other cities, like Barcelona and Rio, which are looking to equip their trams with it. In Sweden, Elways has deployed a test road section near Arlanda Airport in Stockholm. Elonroad, one player that is the most ahead in the game in this type of technology, currently operates a 1km section in Lund in southern Sweden on which it manages to load several categories of vehicles.

Finally, the last technology type is based on induction, which offers contactless vehicle charging. A receiver coil placed under the chassis connects with a loop integrated into the roadway, and the energy is transmitted by a magnetic field. Many trials are now being carried out around the world, while power limitation remains the major obstacle for induction. VINCI subsidiaries – Omexom and Eurovia – are currently running pilot projects in Karlsruhe and Cologne with the Israeli start-up ElectReon, who were originally behind this new technology.

Electrification: the obvious next step

The advent of electric mobility is no longer a speculative horizon or an epiphenomenon. While 100% electric vehicles now represent around 10% of total car sales worldwide, many manufacturers have set very ambitious electric vehicle sales targets for 2030-2035. With this in mind, the electrification of road infrastructure appears as a natural progression, thus rendering possible the reduction of certain obstacles to adopting electric mobility. The main attractions of Electric Road Systems (ERS) are that battery size can be reduced (an ERS truck needs a capacity of 350 kWh compared to 1,200 kWh for a “classic” electric truck), there’s a drastic reduction in the number of charging stations required, and of course, overall, a major reduction in GHGs and the need for raw materials that make up the batteries, such as lithium, nickel and cobalt (the reduction in CO2 emissions is estimated at 87 % compared to a diesel fleet and 64% compared to an “all-battery” truck scenario, whose raw materials needs come in at 1.7 Mt over 20 years). These systems offer road hauliers operational advantages compared to battery-powered vehicles: reduction in vehicle downtime for recharging, better payload and reduction in the acquisition price of vehicles (a third of the price is for the battery).

Based on the essential physical principle that electricity is transported better than it is stored, ERS aim to achieve an attractive objective: less battery for more range.

Important barriers to overcome

Despite the technical soundness of electric road systems, some sizeable obstacles remain. The first relates to the vehicles themselves, which must be adapted regardless of the technology used. “The automotive industry is so busy with making batteries, making software, so that confronting them right now with inductive charging is a priority which is far away. The spirit of this project is to concentrate first on the technical challenges of demonstrating that it works.” explains Mauricio Esguerra, CEO and co-founder of Magment in the New York Times.

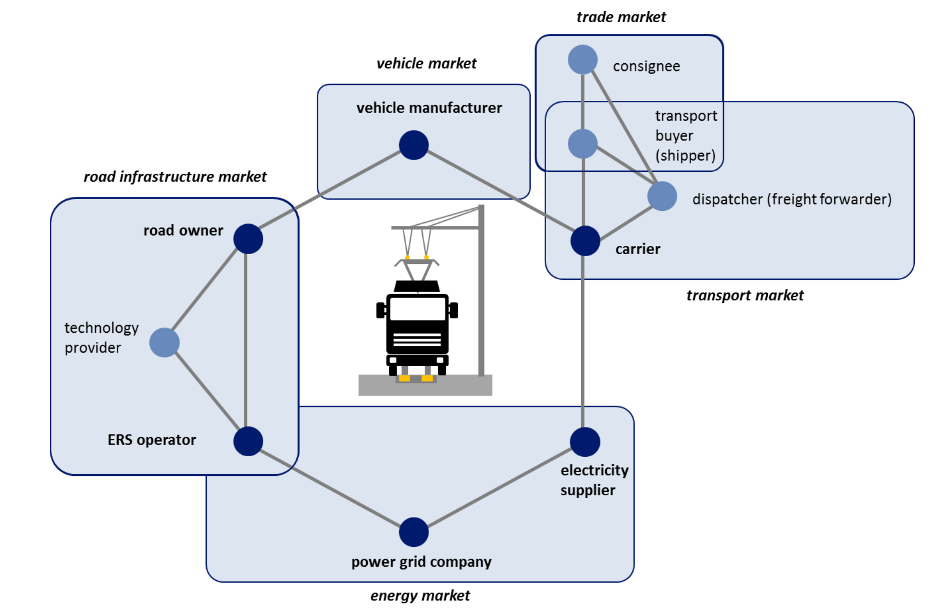

The other major obstacle concerns the governance framework for electric road systems, which is at the crossroads of many markets that are not used to working together, with some highly regulated and others less so. “The introduction of ERS will depend on government support, balancing the business prospects of the transport market and the energy market,” says a report from CollERS: Connecting countries by Electric Roads, a Swedish-German collaborative project.

source: CollERS

Political coordination needed

Apart from the technology, the political dimension behind developing electric roads is essential. In France, the government has led three working groups on electric motorways, covering issues and strategies, technical solutions, and full-scale testing. The initiative led to a call for proposals for ERS projects, as part of the 4th section of the Programme d’Investissement d’Avenir (PIA 4, or Investments for the Future Programme). One of the working groups’ reports states that “The ERS may – or may not – be European, as the long-distance journeys of HGVs and LCVs cross Europe in all directions.” In this context, the CollERS project is exemplary. The results (detailed here) highlight a number of driving forces related to trans-European collaboration:

- Demonstrate the effectiveness of ERS.

- Promote strategic cooperation between countries.

- Foster national ERS roll-out thanks to European synergies.

- Pave the way for the integration of ERS into EU legislation.

Roads as producers of energy?

Apart from conducting electricity, the roads of tomorrow could also be used to produce energy, thus putting their surface coverage to good use. As such, a large number of solar road projects (like Solaroad or WattWay) that operate as photovoltaic panels have come to light, however, with mixed results. Solar canopies for motorways appear more promising. Developed by the Austrian Institute of Technology, they could kill two birds with one stone by generating electricity while also cooling the road. At Eurovia, Power Road technology aims to capture thermal energy from solar radiation and transmit it to surrounding infrastructure via a heat pump system. Others are exploring the potential of highway wind energy, whose yields would be improved by moving vehicles.

Whatever the technology, roads are evolving and are now seeking to play their part in the energy transition.