The appeal of decentralization

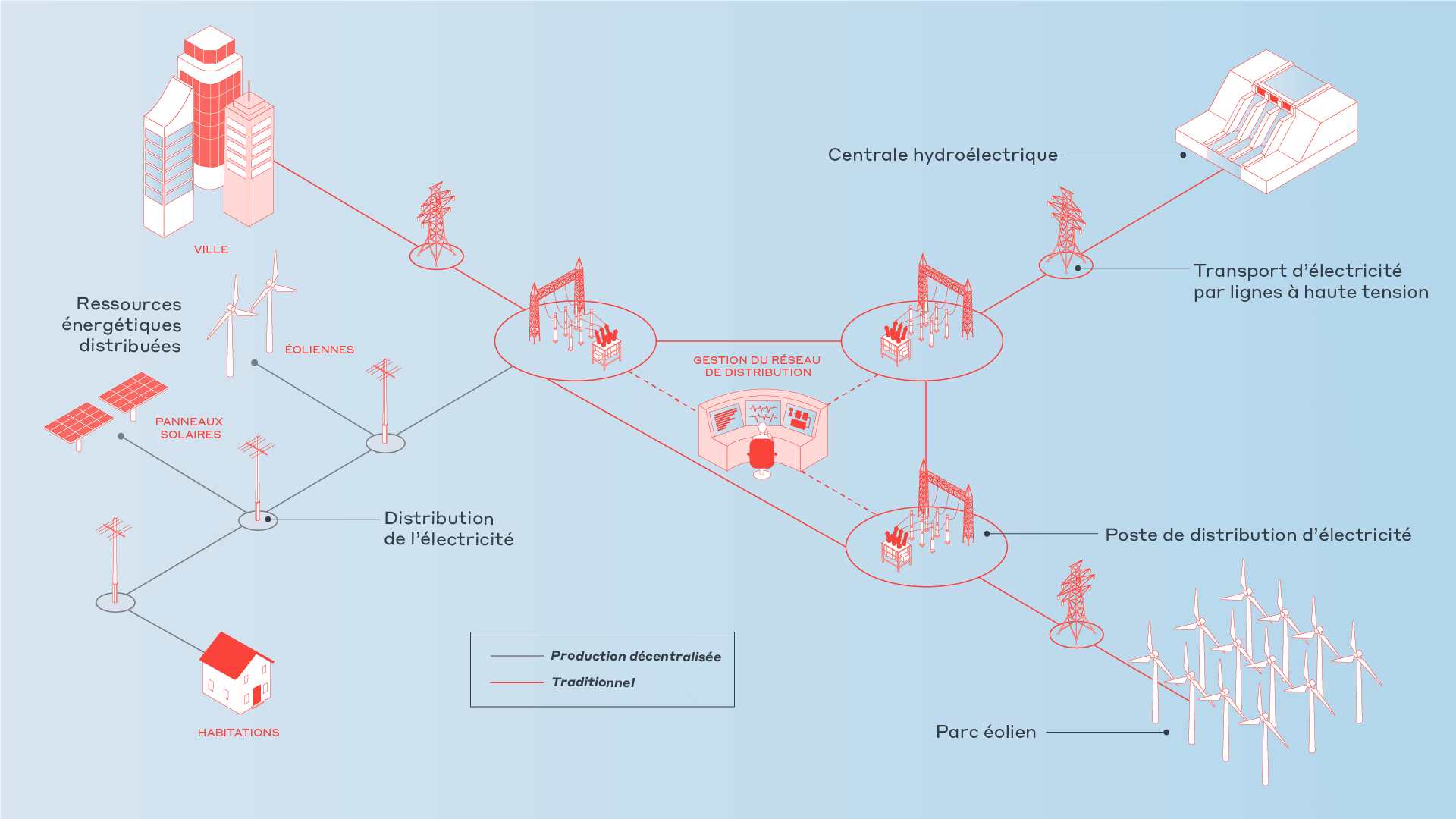

Since the second world war, centralized power grids have been the norm in so-called developed countries. Regardless of the energy type, they are based on large power plants which make energies of scale a possibility and facilitate energy distribution. However, this proven model is now facing new decentralized competition, mainly driven by two technological changes: the widespread development of renewable energy and the emergence of smart grids. With the former, imagine multiple energy production points which are more modest in size, like personal photovoltaic sources and local wind power (on a neighbourhood or municipality level). Meanwhile with the latter, the imaginable becomes imaginable, as the extremely complex task of effectively managing a decentralized network is now a possibility. Both are also driven by social movement, which is pushing towards greener and more local energy sources, but also towards new energy autonomy.

source : wsp

Your own personal profitable technology?

Long hampered by the prohibitive yields of solar and wind power, decentralization is now gaining traction thanks to a radical drop in prices. A recent study by iClimatearth uses California as a case study: it estimates that a self-sufficient electrical energy home (including electric car) translates into annual savings of $7,641 compared to a conventional gas-heated home. According to IRENA (the International Renewable Energy Agency), the costs of solar energy have fallen by 85% between 2010 and 2020. Self-consumption is also driven by increasingly prohibitive energy prices. In France, 100,000 individual households were connected to the network in 2021, compared to 14,000 in 2017. This appetite nevertheless raises the question of the initial investment required, which is likely to favour the wealthiest households and accentuate the energy divide. In the UK, the solar panel market is on the up, even though 6.5 million households are affected by fuel poverty.

Huge investments

Huge investments are required to implement smart, decentralized electricity networks. The European Commission estimates that $70 billion will be required from now until 2030 for grid expansion plans. In India, the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme foresees investments of $40 billion. Meanwhile, the IEA estimates that investments must reach $800 billion annually in order to achieve the flexibility necessary for the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario.

Network management: a technological paradigm shift

Apart from adopting new energy sources, decentralization raises the question of management. With the proliferation of energy sources (and therefore data), the intermittency of renewables and even new forms of electricity consumption (in particularly for electric vehicles), a more agile, responsive and distributed infrastructure is required. “Smart grids” often enter the conversation, which refer to all the different types of technology which go into making these intelligent networks.

- Data-orientated devices

The first step is to have precise and total visibility on the state of the network. As such, IoT or Edge computing solutions naturally accompany the decentralization logic. Smart meter roll-out (like Linky) is part of this movement. Edge Computing – which consists of processing data close to its source – is also essential. The NAZA project(Nouveaux Automates de Zone Adaptatifs) developed by RTE, is preparing to deploy sensors with predictive control algorithms on the network, which can automate congestion management and therefore increase capacity to accommodate renewables.

- A small digital revolution

In a decentralized energy management system, an increase in data and AI integration naturally leads to new software needs. DERMS (Distributed Energy Resources Management System) which gives rise to real competition between major industry players. Schneider Electrics recently acquired Autogrid with the aim of injecting more than 1,000 GWh of renewable and distributed electricity resources into the grid over the next 10 years. GE Digital and Siemens are also among the leaders in a market estimated to reach $23 billion by 2026. Digital solutions are also developing for individuals (and companies) who are new energy producers. In Switzerland, ETH Zurich conducted an experiment using blockchain to facilitate peer-to-peer energy trade. Meanwhile, less futuristic self-consumption management solutions like MyLight Systems are all set to develop.

- Storage capacities and two-way networks

Intelligent network management does not resolve the issue of storage, which is essential for overcoming the intermittency of renewables and avoiding “waste”. With decentralized energy networks come the development of batteries for individual users, such as Tesla’s Powerwall and complete solutions (panels, storage, software) from enphase. At a network level, providers are also getting in on the action, as evidenced by RTE’s Ringo experiment, which consists of deploying a large-scale battery network to deal with intermittency. Finally, the growing popularity of electric mobility suggests a rise in multidirectional V2G (or vehicle-to-grid) terminals such as those from Nuvee, which transform vehicle batteries into storage capacity for the entire network.

Developing countries shunning centralization?

In developing countries – and particularly in Africa where electricity coverage is still far from being total, decentralized networks can help locals overcome often ineffective local authorities and provide local-level structurisation. In Nigeria, whereby 60% of the country is covered by the electricity grid, a newly created citizens’ initiative for renewable energy follows in this direction. The African Development Bank recently invested $164 millionto develop decentralized renewable energy in Ghana, Guinea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Tunisia. However, there remains immense room for manoeuvre: Africa produces around 5TWh annually from solar energy out of a potential of more than 60 million.

Local ownership on the up

Apart from self-consumption, energy decentralization can be based on powerful community logic that promotes the implementation of local “microgrids” which can meet specific local needs. According to the State of the Energy Union report, at least 2 million people in the EU are involved in 7,700 energy communities, accounting for 7% of renewable energy production. Meanwhile, Energie Partagée created a map of the French energy ecosystem, detailing the variety of projects set up, from a Cévennes hydroelectric installation to photovoltaic farms in the Pyrenees.

The documentary We The Power produced by Patagonia gives an insight into certain citizen-led initiatives, from Germany to London, via Spain.

A renewed role for national networks

For reasons of equity at a national level and security of supply, it remains difficult to envisage situations in which consumers and producers could do without public electricity distribution and transmission networks altogether. With developments ongoing, the nature of national networks gives them a decisive advantage over a cluster of closed distribution systems. Resources can be pooled and production – and thus, consumption – can be increased. As collective self-consumption initiatives are spreading – and more broadly speaking, citizens and communities are mobilising within energy communities, this heralds a smarter use of central networks, rather than an alternative one.

“The use of energy communities should not be synonymous with energy communitarianism”

— Arnaud Banner, Technical Director at Omexom

On the grapevine

“The technological transition which can bolster the energy transition still remains to be built. For integrated networks of tomorrow to be mastered, they will essentially have to combine power electronics, control-command systems responding to the millisecond and artificial intelligence.”

— Thierry Lepercq, Vice-president at Engie for PwC